The effect of clinical silos on teamwork in practice

Healthcare is a rapidly evolving industry. Unfortunately, the rapid pace of change can result in suboptimal outcomes in the form of increased costs, variable quality, changes to treatment processes and pathways, and a fragmentation of care that creates opportunities for adverse events to occur (Patton et al., 2003, Ash et al., 2004, Graber, 2004, Han et al., 2005, Nawaz et al., 2014).

Increasing specialization and sub-specialization results in greater division of expertise and the creation of gaps in treatment delivery, which creates opportunities for key information to slip through the cracks (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2006).

Pettker et al. (2009) highlighted problems related to the utilization of specialized teams in healthcare, noting that weaknesses in coordination and communication should be expected given that medical stakeholder groups are trained in “isolated silos, with differing languages and contrasting perspectives”. To counter the silo effect, specialty languages and multi-dimensional perspectives, “greater collaboration and teamwork among various disciplines and specialties is necessary” through inter-disciplinary care and collaborative teamwork (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2006, Nawaz et al., 2014).

Thylefors et al. (2005) have shown that the greater the inter-dependence and the better the co-operation between team members, the greater the efficiency achieved. However, literature highlights that developing a true team takes effort (Smith et al., 2018). Zwarenstein et al. (2007) identified several deficiencies commonly observed in care teams:

Absence of knowledge of colleague’s names

Absence or ambiguity of colleague’s roles, title and credentials

Lack of shared profession specific knowledge base

Communication tends to be one way with little reciprocity.

In inter-professional teams, different disciplines bring with them different concepts and perspectives regarding high-quality patient care, as well as different priorities of the patient’s needs and corresponding responses (D'amour and Oandasan, 2005). Unfortunately, the very nature of most education programs for healthcare providers focuses their training on specific conditions, techniques and paradigms of care creating or further contributing to silo based perspectives and care.

Consequently, Zwarenstein et al. (2007) developed a structured communication tool focused on promoting collaborative communication between healthcare professionals, noting that continuously introducing oneself by name and role during inter-professional patient interactions reduced anonymity and role confusion.

An important element of inter-professionality is the coming together of different disciplines with the common team goal of providing integrated cohesive responses to the needs of patients and carers. For this to function, disciplines must abandon silo-based perspectives and thinking in favor of alternative approaches, open discussion of potential solutions and collective agreement on the plan of care. Each stakeholder must be open to continuous learning and alternative perspectives from their peers. As such, inter-professionality incorporates both practice and education elements to care delivery where team members “collaborate synergistically” (D'amour and Oandasan, 2005).

Adamson et al. (2018) proposed a four-stage model of teamwork characterization incorporating elements of inter-professional empathy that can be insightful for leaders to evaluate their unit(s) and staff:

Conscious interactions: relationships that display authenticity, warmth and respect for each team member. Interactions between team members are based on the conscious goal of getting to know, support and help teammates.

Dialogic communication: two-way interactive communication, i.e. ‘talking with’ not ‘talking to’ team members. Team members seek to understand the perspective of each other. Each team member is open and honest, actively listens and reflects on the ideas and perspectives discussed without judgement.

Consolidation of understanding: Team members share personal and professional insights that reveal their personal perspectives, beliefs and personality. Team members develop greater familiarity with each other and grow to understand, appreciate and accept differing perspectives and priorities, creating the foundation for negotiation where needed.

Nurturing the collective spirit: each team member recognizes their responsibility to the team and understands how to balance their personal perspectives and beliefs with the needs and goals of the team. The synergistic effect of the team is recognized, as well as the emotional, social and psychological benefits of working collectively towards the team goal. Team members exhibit signs of volunteerism, workload sharing, peer supported co-operative work, and placing the team goals and product ahead of their own.

This model may sound like a nice to have, not a need to have. But the quickly changing hospital environment demands us to evaluate our realities and goals, as well as the processes that contribute to, or prevent, our progress.

Since we can only accurately treat what we correctly diagnose, you might find the following activity helpful in understanding the teamwork on your unit(s).

Activity

Task: Use this four-stage model to evaluate staff interactions and teamwork on your unit(s). How do they rate? We’ve provided a downloadable score card for you to print off and use: here.

Question: Do the current processes and workflows on the unit support or undermine the inter-professionality on your unit(s)?

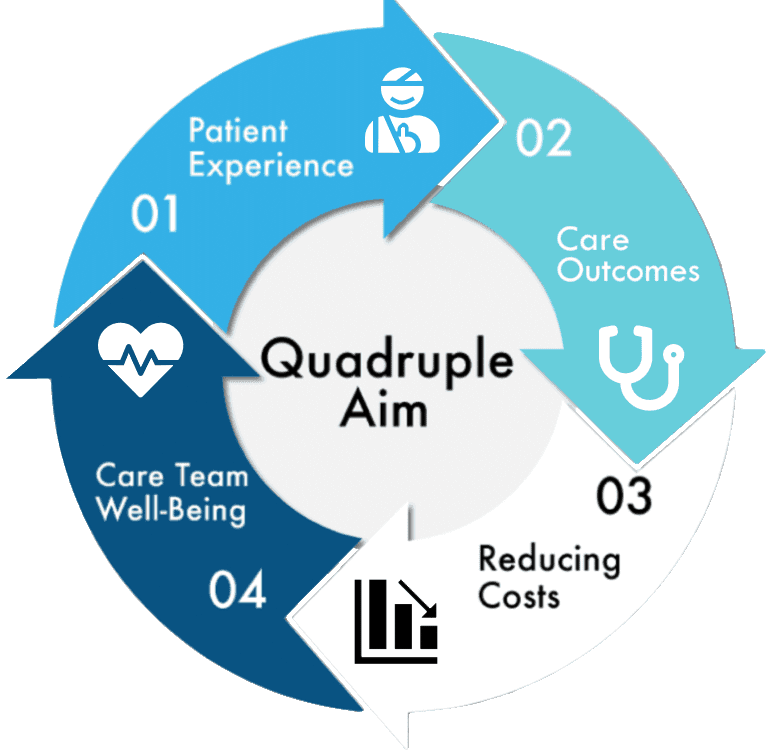

Question: Do you see any correlation between unit inter-professionality and unit outcomes vis-à-vis the quadruple aim?

Thinking-ahead: What practical steps can be taken to improve staff interactions and teamwork, cognizant that staff are already over-worked and burned on most units today?

References

Adamson, K., Loomis, C., Cadell, S. & Verweel, L.C., 2018. Interprofessional empathy: A four-stage model for a new understanding of teamwork Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32, 752-761.

Ash, J.S., Berg, M. & Coiera, E., 2004. Some Unintended Consequences of Information Technology in Health Care: The Nature of Patient Care Information System-related Errors. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 11, 104-112.

D'amour, D. & Oandasan, I., 2005. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: An emerging concept. Journal of interprofessional care, 19, 8-20.

Graber, M., 2004. The Safety of Computer-Based Medication Systems. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164, 339-340.

Han, Y.Y., Carcillo, J.A., Venkataraman, S.T., Clark, R.S.B., Watson, R.S., Nguyen, T.C., Bayir, H. & Orr, R.A., 2005. Unexpected Increased Mortality After Implementation of a Commercially Sold Computerized Physician Order Entry System. Pediatrics, 116, 1506-1512.

Nawaz, H., Edmondson, A.C., Tzeng, T.H., Saleh, J.K., Bozic, K.J. & Saleh, K.J., 2014. Teaming: An Approach to the Growing Complexities in Health Care Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American Volume), 96, e184.

Nembhard, I.M. & Edmondson, A.C., 2006. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27, 941-966.

Patton, G.A., Gaffney, D.K. & Moeller, J.H., 2003. Facilitation of radiotherapeutic error by computerized record and verify systems. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics, 56, 50-57.

Pettker, C.M., Thung, S.F., Norwitz, E.R., Buhimschi, C.S., Raab, C.A., Copel, J.A., Kuczynski, E., Lockwood, C.J. & Funai, E.F., 2009. Impact of a comprehensive patient safety strategy on obstetric adverse events. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 200, 492.e1-492.e8.

Smith, T., Fowler-Davis, S., Nancarrow, S., Ariss, S.M.B. & Enderby, P., 2018. Leadership in interprofessional health and social care teams: a literature review. Leadership in Health Services, 31, 452-467.

Thylefors, I., Persson, O. & Hellström, D., 2005. Team types, perceived efficiency and team climate in Swedish cross-professional teamwork. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19, 102-114.

Zwarenstein, M., Reeves, S., Russell, A., Kenaszchuk, C., Conn, L.G., Miller, K.-L., Lingard, L. & Thorpe, K.E., 2007. Structuring communication relationships for interprofessional teamwork (SCRIPT): a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 8, 23.

Keep Exploring Our Work